by John A Eney, eneyair@olg.com

Originally Published in Skyways Journal Magazine

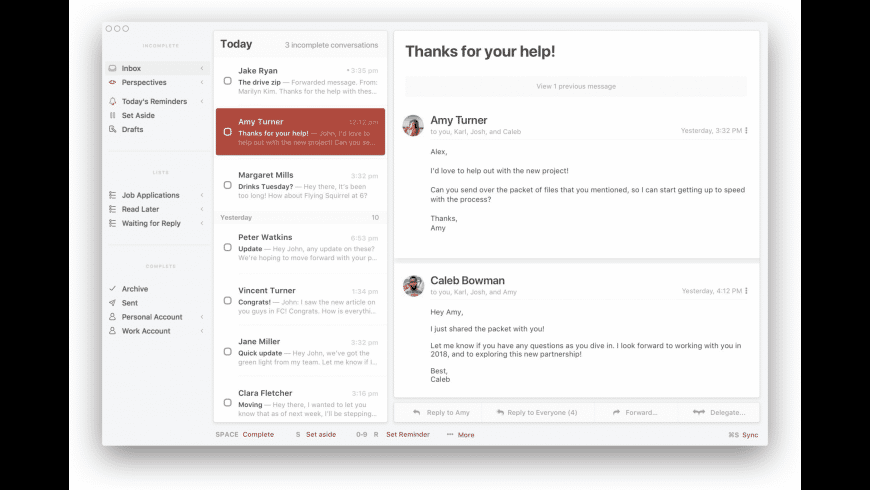

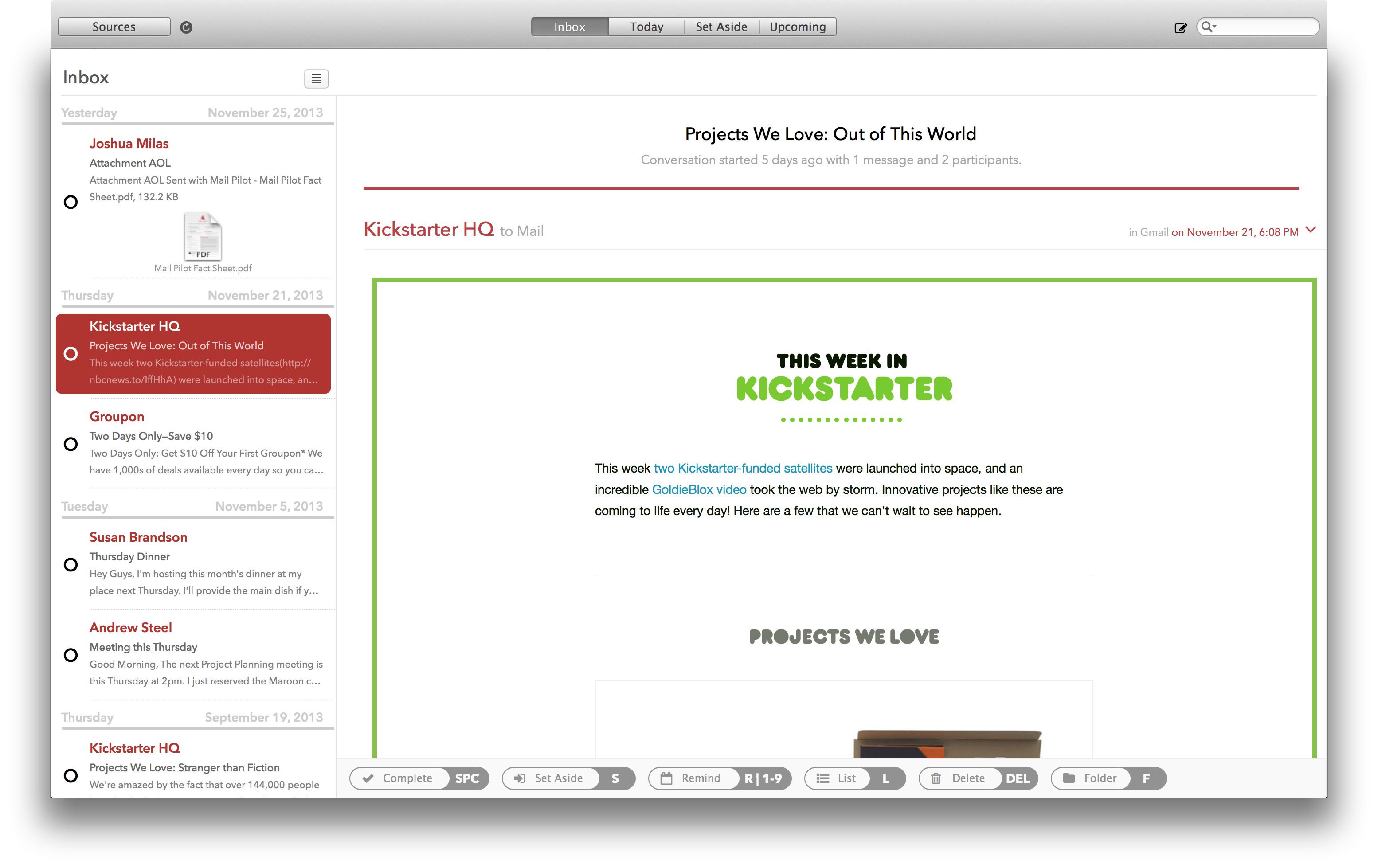

Daily Mail posted a video to playlist Heartwarming videos. April 4 at 6:05 AM This pilot faked a problem with the plane in order to surprise his girlfriend! The Mail Pilot is a Mickey Mouse cartoon that debuted on May 13, 1933. 1 Summary 2 Characters 3 Comic strip adaptation 4 Releases 4.1 Television 4.2 Home video 5 Gallery Mickey the mail pilot is entrusted with a chest of money. He battles rain and snow, but his biggest battle is against Pete, who has a plane equipped with a machine gun and a harpoon cannon. Mickey's plane quickly loses its. Pilot resources, including email templates and sample feedback survey questions; Switch to Teams from Skype for Business, a quick-start guide designed to help Skype for Business users get started with Teams; 5. Conduct your pilot. With all the logistics in place, you're now ready to begin your pilot. Mail Pilot users can quickly manage and productively organize their inboxes with a simple, task-oriented approach, tailored for the desktop.

Lt. George Boyle in JN-4H 38262 starts his takeoff from

Washington, DC with the first scheduled US air mail on May 15,

1918. Photo USAF 34145, Editor’s collection

May 15th of 2008 marks 90 years since the inaugural launching of the

first scheduled air mail service sponsored by the United States Post

Office Department. On that fog shrouded mid-May morning in 1918,

President Woodrow Wilson handed his personal letter of greetings to a

very young and relatively inexperienced Army Air Service pilot at

Potomac Park polo grounds in Washington, DC, to be flown to the Mayor

of New York City, via a relay stopover at Philadelphia, PA.

Simultaneously, another Army pilot was departing from Hazelhurst Field

on Long Island, NY, for the same relay handover point in Philly. This

may sound simple to modern readers, but in wartime 1918, with

springtime dense morning fog over the entire northeast coast, and no

available pilots trained in ANY cross country navigation, let alone

instrument flying, this was taking extremely high risk. How this

entire event was conceived, funded, produced and directed, and by

whom, is a well documented tale of political ambitions, technical

naivete, and military courage worthy of a Hollywood movie or TV

miniseries. And this event is today recognized as the seed planting

for the U.S. airline industry we now take for granted.

The prime mover in this birth of the air mail was NOT the pilot

community, nor even the young aircraft industry. It was one Otto

Praeger, Second Assistant Postmaster General, himself a non-flyer who

simply sought to improve the speed of intercity mail shipments then

carried exclusively by train. Oblivious to the limitations of 1918

aircraft technology and performance, he convinced his boss, Postmaster

General Burleson, to suggest to the President that the Secretary of

War could order the Army Air Service to assume this new role, starting

in just a matter of several days! And so the executive orders were

quickly passed to War Secretary Newton D. Baker, thence to Chief of

the Army Air Service Col. “Hap” Arnold, who promptly summoned his

Executive Officer to his desk, one Major Reuben H. Fleet. The orders

were dated May 3, 1918. The orders read to initiate daily air mail

service between Washington and New York on May 15, 1918. Hap Arnold

and Reuben Fleet were professional soldier-pilots who knew all too

well that you didn’t say “no” to the President, and they had to salute

and carry out the orders as best they could, given no suitable

airplanes, and no pilots with adequate cross-country navigational

training in good weather or bad.

And it is in major crises that clever men rise to become great men.

In this situation, Fleet needed to overcome his Air Service

inadequacies in men and equipment in just twelve days to avoid

embarrassing the President of the United States and the Air Service in

the eyes of the news media and the American public. His first action

was to request Col. Edwin A. Deeds, Chief of Air Service Production,

to place an immediate order to the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor

Corporation, Garden City, Long Island, NY, for (6) new specially

configured JN-4H “Jenny” training biplanes with doubled fuel tank

capacity and without controls in the front cockpit, which was to be

covered over as a mail pit. This would give the mail plane Jenny

twice its standard range of only 88 miles so it could in fact make the

trip from DC to Philly nonstop. The “H” model Jennies were powered by

the 150 hp Hispano-Suiza (“Hisso”) liquid cooled V-8 with enclosed

overhead cams and automatic valve lubrication, making them far more

reliable than the earlier 90 hp Curtiss OX-5 V-8s with open, hand

lubricated valve actions. Curtiss simply added a second standard

terneplate fuel tank in tandem with the regular tank between the

firewall and the mail pit. The airplane problem was solved in short

order through this instant cooperation between the

engineering-educated Fleet, his parent command staff, and the already

humming production line at Curtiss. (Could this ever happen today?)

Fleet then hand picked by name several of his best Army instructor

pilots who could at least dead-reckon with a road map in lieu of any

aeronautical charts which did not then exist. He had the new special

Jennies assigned to these four pilots with one for himself. The

airplanes were to be ferried to the necessary fields of deployment by

15 May. Fleet flew himself down from NY to DC early in the morning of

the 15th, delayed considerably by very low ceilings and poor

visibility all the way. He flew Jenny number A.S. 38262 into the polo

grounds before a waiting crowd of news media, onlookers, and a very

impatient President Wilson and his attending staff of Secret Service

guards. He motioned to his in-place enlisted men to service the

airplane for the flight back to Philly, and was then informed that the

pilots he had selected were to be replaced by two other fresh

graduates from Air Service primary flight school who happened to be

sons of .politically important officials. in the Wilson

Administration. The politically selected pilot for the DC to Philly

leg that morning was Lt. George Boyle, and the southbound pilot from

Long Island was to be Lt. James Edgerton, neither of whom had ever

flown out of clear sight of their home training fields. Once again

the professional soldier, Fleet realized he had again been snared by

political forces opposing both sound reason and sound physics. He

proceeded to brief Lt. Boyle on how to follow the mainline railroad

tracks that ran from DC to Philly, in a fairly straight northeasterly

heading, unhindered by any mountains or tunnels. All he needed was

the road map from Fleet, and the magnetic compass in the JN-4H cockpit

instrument panel. Potomac Park was a tiny peninsula extending from

the eastern shore of the Potomac River close to the center of DC and

parallel to the river, near the Jefferson Memorial and across from

what is now the Pentagon and Reagan National Airport.

With appropriate ceremony, the President made his public sendoff

speech and handed his personal letter to the crew chief loading the

mail pit while Lt. Boyle suited up and mounted the rear seat of

38262. The Army guards drew the crowd away from the Jenny so that the

engine could be hand propped to start. Well, the engine failed to

start after many tries. Fleet told the crew chief to dipstick the

fuel tank since even brand new float gauges had been known to mislead.

The tank dipped near empty. In the rush of the moment that morning,

Mac for word textbook align tool. they forgot to refuel the airplane after Fleet landed it.

With the fuel soon topped in both the tandem tanks and the mail bin

loaded and the hatch strapped closed, the Jenny now started on the

first swing of the prop and Lt. Boyle waved to have the chocks pulled

from his brakeless spoked wheels. He blasted the power to lift the

tailskid free of the turf polo field and turned to start his takeoff

into what little wind there may have been in that foggy condition.

The crowd cheered as his Jenny cleared the tall trees surrounding the

periphery of Potomac Park and disappeared into the mist as it flew off

toward destiny in Philly.

Major Reuben H. Fleet, just arrived at Potomac Park in

Washington, DC from New York via Philadelphia in Army Air Service

Jenny 38262 for the start of the first scheduled US air mail service

on May 15, 1918. President Woodrow Wilson and other officials were on

hand to witness this historic event. Photo: USAF 34209,

Editor’s Collection

Well, sort of. Astute witnesses at the departure candidly reported

later that the sound of the departing Hisso engine seemed to indicate

that Boyle was not following a straight-out northeastern heading

through the mist, but was circling around at first. But, no matter

that, the southbound Jenny from Philly with the mail from New York

soon landed and the headlines across the nation proclaimed the

successful start of scheduled U.S. air mail service. A short time

later, a phone call was received at the polo field communications

tent. It was Lt. Boyle. He had gotten lost and made an emergency

landing in a farmer’s field. The stub crops caught the landing gear

spreader bar and the prop dug in and flipped the JN onto its back. He

was unhurt. The mail was not damaged or lost. His location was a

farm in Waldorf, MD, southeast of Washington, not northeast. He had

followed the railroad tracks, but the wrong tracks. A branch line off

the mainline northeast railroad right-of-way went south to a coal

powerplant at Popes Creek, through the little town of Waldorf. But

nonetheless, the other legs of the DC-PA-NY air mail route had been

flown successfully that day, and the champagne corks were already

popped. Today, NASA would call this a 90% mission success, and indeed

it was that.

Standard JR-1Bs, designed from the outset as mailplanes,

replaced the Army Jennies when the Post Office Department took over

the air mail from the Army Air Service in August, 1918. Photo:

Editor’s Collection

The Army Air Service continued to operate one trip per day from DC to

NY along this 218 mile route using the mail-configured JN-4Hs on a

6-day week, with Sundays off (for the pilots, not the ground crews) up

until August 12, 1918, at which time the Post Office Department took

over the entire operation, using specially designed mail planes

ordered from the Standard Aircraft Company of Elizabeth, NJ. These

Standard JR-1B models were also Hisso powered, like the Army JN-4Hs,

but had a 200 pound mail capacity and a range of 280 miles. While

rarely if ever depicted in aviation history journals, these Standard

JR-1Bs remain milestones in being the first civil aircraft specified

and procured by the U.S. Government. According to Reference (1), the

scorecard of statistics on the mission performance of the Army pilots

and their (6) Jennies during their May-15-August 12 tour of duty on

the northeast corridor route were as follows:

- 92 percent of schedule flights successfully completed.

- 193,021 pounds of mail carried

- 128,225 route miles flown without a signel fatality

All this was accomplished without aeronautical charts, no radios, no

gyros, in open cockpits, and all during the height of the east coast

summer thunderstorm season.

This first air mail service “experiment,” using Air Service pilots and

JN-4Hs, owed a great deal to the management skills of a non-flying

Army ground officer, Captain Benjamin B. Lipsner. So impressed was

Otto Praeger with Lipsner’s masterful coordination of the air mail

operation, he asked Lipsner to resign from the Army and sign on as

the head of the air mail for the Post Office Department. Lipsner had

wanted to see action in France before the war ended and hesitated to

resign his commission, so Praeger wrote to War Secretary Baker

requesting Lipsner be granted a leave of absence, but this request was

denied. Shortly thereafter, the Army did in fact allow Lipsner to

resign and assume his new civil service position as the first

Superintendent of the Aerial Mail Service (Reference 1). The new air

mail chief’s first official act was to request the Post Office order

to (6) of the Standard JR-1Bs mentioned earlier.

The workhorse of the air mail service in the US, the

Liberty-powered US-built DH-4. Photo: Editor’s Collection

The new Air Mail Service undertook immediate plans to methodically and

cautiously expand its service to other cities in other states toward

the Midwestern industrial population centers of Cleveland and

Chicago. This New York-Cleveland schedule began in May of 1919. In

September of that year, it was extended to Chicago. This was the

prelude toward realization of the ultimate goal of the Post Office,

which was a true transcontinental air mail route from New York to San

Francisco. The airplane of choice for these expanded routes with

longer ranges was the rebuilt ex-Army DeHavilland DH-4, a British

design built under license by several manufacturers in the United

States, and intended to be America’s bomber at the Western Front in

France before the war ended in November, 1918. These DH-4s had been

stripped of wartime armament and had all new landing gears and

fuselages made of steel tubing. The redesign for mail service

included relocating the pilot.s cockpit well aft of the engine and

fuselage fuel tank, whereas the original wartime design had placed the

cockpit underneath the upper wing centersection and sandwiched

(sometimes literally) the pilot between the Liberty V-12 engine and

the main fuselage fuel tank behind that cockpit. (It was the British

wartime original design that had earned the nickname of “Flaming

Coffin” due to high fatality rates in crash landings.) These DH mail

planes were redesignated as DH-4Ms, and many of these conversions were

performed under government contract by the Boeing Airplane Company in

Seattle, WA. It was also during this transition to DH-4Ms that the DC

terminus for the air mail was located on College Park Airport in

College Park, MD, just outside the northeast border of the District of

Columbia. That site of many aviation firsts, including the

demonstrations and sales of Wright Brothers’ aircraft, remains today

as the oldest continually active airport in the United States, going

back to 1909.

The old and the new of mail delivery.The Pony Express was the

fastest means of sending mail during the great western movement of the

19th century United States. The airplane, symbolized by the DH-4

mailplane in this photo, took the lead in speed in the early 20th

century. Photo: Editor’s Collection

Loading mail into DH-4 No. 68 with its big Liberty engine

warming up. Photo: Editor’s Collection

Looks like the end of the line for old number 400; or, maybe

she’s tucked away in an old barn somewhere, long forgotten and just

waiting to be found! Photo: Editor’s Collection

Several attempts were made to improve the DH-4’s load-carrying

ability including the addition of Bellanca lift struts. Photo:

Editor’s Collection

Another load-carrying improvement to the DH-4 was this big

winged modification by the Whitteman Co. in 1921. Photo: Editor’s

Collection

Mail Pilot Travel Centers

L.W. F. (Lowe, Willard & Fowler) converted the workhorse

deHavilland DH-4B into a twin engine mailplane with disappointing

results. Service ceiling was reportedly 1,500 feet, and takeoff speed,

cruising speed, and landing speed were the same! Photo: Editor’s

Collection

The transcontinental air mail service route was completed in

September, 1920, extending westward through Omaha, North Platte,

Cheyenne, Rawlins, Rock Springs, Salt Lake City, Elko, Reno, and into

San Francisco at Crissy Field. Air mail flying remained a

daytime-only operation up until 1921, though maintenance and overhauls

proceeded around the clock at each waypoint shop hangar. Night time

air mail flights were first tried as an experiment starting on

February 22, 1921. On that date, two pilots flying DH-4s left from

San Francisco eastbound, and two other pilots left from Hazelhurst

Field on Long Island westbound, also both in DH-4s. The goal was for

at least one member of each team to successfully link up at a transfer

relay point in Chicago within a total elapsed time of 36 hours, flying

through the night as well as day. The westbound team had one ship

forced down by weather in western PA, a mountainous region with

unpredictable weather still known today by airline pilots as “hell’s

stretch.” The two separated east bound ships had changed pilots at

Reno and again at Salt Lake City and Cheyenne, and North Platte, where

the relief pilot was one Jack Knight. Weather was ominous as Knight

took off for Omaha, but news accounts of the air mail events were

already causing enthusiastic residents along the prescribed route to

light huge bonfires in open fields to guide the pilots through the

night. By 1 am, when Knight made the outskirts of Omaha, he found

the entire city lit up for his guidance, and he landed at the

destination turf landing field between rows of old 55-gallon drums of

gasoline set afire to light the runway for him. He had flown 276

miles and was due to be relieved for the last leg eastward into

Chicago. But that relief pilot was weathered in at Chicago and could

not get to Omaha. Knight was totally unfamiliar with the leg from

Omaha to Chicago, but after a hot slug of coffee, decided to re-man

his DH and press on to Chicago himself, with the help of the bonfires

set along the way. The station manager gave him a Rand McNally road

map of the 435 leg to Chicago, via Des Moines and Iowa City. Knight

overflew Des Moines due to weather and landed for fuel at Iowa City in

a snow squall. After that brief stop at around 5 AM, he again took

off for the last 200 miles into Chicago through light snow and icing

conditions which severely threatened weight and drag of the strut and

wire covered DH. At early dawn light, he spotted the railroad main

line parallel tracks and followed them in to Maywood Airport in

Chicago where he landed and turned over the mail to the eastern route

pilot at 8:40 am on February 23rd, 1921. The nation had been linked

by overnight air mail with an elapsed time of just 33 hours and 25

minutes, with just under 26 hours of actual flying time. Jack Knight,

the air mail pilot, became a national hero and was featured in

newsreels at movie theaters coast to coast. An elated Otto Praeger,

speaking for the Post Office Department, made a public announcement

that overnight air mail service nationwide was now a regular scheduled

operation and that a radio network of ground stations would be

promptly activated during the 1921-1922 period to hasten the exchange

of weather reports needed for the safety of both pilots and ground

crews.

Jack Knight became a national hero for his daring role in the

first overnight transcontinental air mail service.

Photo: Editor’s Collection

The first air mail flights in the US authorized by the

Postmaster General were made by Earle Ovington at the International

Aviation Meet held at Garden City Estates, Long Island, NY from

September 23 to October 1, 1911. A temporary post office was set up

and Ovington carried the mail sack on his lap while flying his Bleriot

monoplane on the 7-mile trip to Mineola, NY. Here, Postmaster General

Frank H. Hitchcock hands the first sack of air mail to Ovington

seated in his Bleriot. The Cradle of Aviation Museum on Long Island

has a reproduction of Ovington.s Bleriot. Photo: Editor’s

Collection

Early attempts at carrying air mail and, in this case, parcels

as well, were mostly short-lived. Considering the type of aircraft (an

early pusher biplane), this must have been one of the earliest

attempts. Photo: Editor’s Collection

Mail Pilot App

Standard biplanes carried the air mail for Colorado Airways.

Photo: Editor’s Collection

The Post Office Dept. ordered a mailplane version of the Glenn

L. Martin MB-1 bomber that could carry 1500 lbs. of mail in a bulbous

nose. Six of these huge mail carriers known as the Martin Model MP

were put in service on the New York-Chicago run during the winter of

1919-20, one of the most severe on record. Rough weather and rough

airfields quickly claimed 4 of the MPs and the Post Office transferred

the remaining 2 to the Army. Photo: Editor’s Collection

Three Martin MP Mailplanes await delivery at the Martin factory

in Cleveland. Photo: Editor’s Collection

Martin MP No. 203 was severely damaged at Heller Field, NJ in

1920. Photo: Editor’s Collection

In 1923, after Army experiments with beacon-lighted “airways” proved

viable, the Post Office Department began installing tower-mounted

rotating gaslight beacons every 25 miles along its routes with

emergency landing fields adjacent to each of these beacons, staffed

with mechanics for aircraft servicing and repair. Full

transcontinental air mail service along this lighted airway became a

reality in 1924.

The Kelly Air Mail Act

The Kelly Air Mail Act of 1925 became a watershed event that set into

motion the creation of commercial air mail and passenger travel in the

United States. U.S. Representative Clyde Kelly convinced the

U.S. Congress in February of that year that the government should get

itself out of the air mail business and let private air carriers

compete for contracts to operate various portions of the national

route system already established. The first five Contract Air Mail

(CAM) small feeder route contracts were awarded by Postmaster General

Harry J. New on October 7, 1925. The first contract to actually get

underway was not one of these five, but a later one awarded to one

Henry Ford, the automobile manufacturer in Detroit, MI. Ford had

hired airplane designer William B. Stout, since 1923, to lead the

development of all-metal monoplane transports produced under the

respected Ford corporate name. This air mail contract award for

service between Chicago, Detroit, and Cleveland, hastened the fielding

of the legendary Ford Tri-Motor with its signature corrugated aluminum

skin covering the entire airframe. At first, these air mail contract

carriers were paid by the pound of mail actually carried, but this led

to fraudulent abuses whereby the carriers were mailing bricks inside

mail bags back and forth to up their winnings on invoices submitted to

the Post Office Department. The fee schedule was soon changed and

paid the carriers according to the volume of the mail compartment in

their aircraft. This had a secondary benefit in that it accelerated

the purchase of larger aircraft with larger payload capacities that

eventually included space for paying passengers as well as mail

sacks. The U.S. airline industry was thus born in the process.

The Boeing Model 40A (shown here) and 40B could carry

passengers as well as air mail and were used primarily on routes in

the western US. Photo: Editor’s Collection

The Douglas Mailplanes, M-2s, M-3s, and M-4s (shown here) were

Theyre really, really, really sorry.... developed to replace the aging DH-4s. Photo: Editor’s

Collection

An innovative method of picking up mail in rural areas without

landing was developed by Lytle S. Adams and is shown here in use with

one of Clifford Ball’s Fairchild FC-2s on CAM 11 in 1930. The pickup

system was developed further and used extensively by All-American

Aviation which became Allegheny Airlines. Photo: Editor’s

Collection

U.S. Air Mail usage surged with each new success, and the DH-4Ms

soldiered on in air mail service until they began to wear out. In

1927, the government sponsored a design competition for new, higher

performance mail planes and the winner was the Douglas Aircraft

Company of Santa Monica, CA. They were to produce (51)

Liberty-engined, purpose-built biplanes that carried twice the

500-pound load of the DHs and cruised at 175 mph. Those Douglas ships

were designated the M-2 and one survives today fully restored to

flying condition in the Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum in

Washington, DC. Only a couple of mail-configured DH-4s remain in

U.S. collections. The former Paul Mantz-owned DH-4M used in the 1957

Warner Brothers feature film, “The Spirit of St, Louis,” resides now

in the Evergreen Air Museum collection in Tillamook, OR. Another

recently restored DH-4M flies occasionally out of the Historic

Aircraft Restoration Museum at Creve Coeur Airport, west of St. Louis,

Mo. The U.S. Post Office Building in downtown Washington, DC,

contains a little-publicized museum hall deep inside the building

which displays a privately reconstructed DH-4 mail plane and a 1939

Stinson SR-10 Reliant that was used for aerial mail pickup by

grappling hook with the All-American Airways contract carrier for

several years. The Smithsonian NASM has an original American-built

DH-4 bomber on display, fully restored with full military equipment,

not as a mail plane.

As more and more contracts were let for commercial air mail carriers

in various regional feeder routes, more civil aircraft of various

makes and models began to appear in air mail liveries. These included

old Curtiss Jennies (again) as well as new production biplanes with

steel tube construction by such manufacturers as Swallow, Travel Air,

Waco, and Stearman. The Boeing Airplane Company operated a Boeing Air

Transport contract carrier in the Pacific Northwest states, and they

developed their own very large single-engined biplane, the Boeing 40,

which was equipped with a heated and lighted fuselage compartment that

would hold not only mail but two seated and safety-belted paying

passengers in fully-enclosed luxury, with windows on both sides.

Today, there is one Boeing 40 displayed in the Ford Museum in

Dearborn, MI, and a newly restored and fully flyable Boeing 40 owned

by Mr. Addison Pemberton at Spokane, WA. Both are powered by the

original Pratt & Whitney R-1690 “Hornet” 9-cylinder radial engine.

Clifford Ball started flying the air mail between Pittsburgh

and Cleveland in 1927 with 2 Waco 9s in an operation that became

Pennsylvania Air Lines and, later, Capital Airlines. One of the Waco

9s, Miss Pittsburgh, survived, was beautifully restored, and can be

seen today hanging in the Pittsburgh airport terminal. Photo:

Editor’s Collection

Ryan M-1 Mailplanes served Colorado Airways out of Denver.

Photo: Editor’s Collection

National Air Transport Douglas M-3 Mailplanes at Hadley Field,

New Brunswick, NJ on Sept. 1, 1927 inaugurating scheduled

coast-to-coast air express service. Photo: Editor’s

Collection

Pitcairn Aviation Inc. operated CAM 19 between New York and

Atlanta with Pitcairn Mailwings and Super Mailwings like this PA-8.

Expanding south into the lucrative Florida market and north to Boston,

the name was changed to Eastern Air Transport and, eventually, to

Eastern Airlines. Photo: Editor’s Collection

The Curtiss Carrier Pigeon mailplane. National Air Transport

operated 10 of these on the New York-Chicago air mail route. Photo:

Editor’s Collection

Varney Airlines provided air mail service between Elko, Nevada

and Pasco,Washington via Boise, Idaho with six of these Wright

J-4-powered Swallow mailplanes.The pilot is Leon Cuddeback who flew

the first flight on this route on April 6, 1926. Photo: Editor’s

Collection

Square-tail Stearmans including the C-3s (C-3B shown here),

Speedmails, Senior Speedmails, and Junior Speedmails were popular

mailplanes. Photo: Editor’s Collection

The McNary-Watres Act

With small contract mail (and passenger) air carriers operating all

over the country, the U. S. Postmaster General now wielded the most

power in all of civil aviation. Such was realized by the new

Postmaster General, Walter Folger Brown, appointed by the newly

elected President Herbert C. Hoover in 1929 (References 1-6). Brown

seized the opportunity to implement sweeping changes toward creating a

nationwide network of commercial airlines who were self supporting on

passenger revenues and who did NOT need to be dependent on air mail

subsidies for survival and profit. In 1930, Brown convinced a majority

in Congress to pass legislation that came to be known as the

McNary-Watres Act on April 29th, which contained provisions for the

Postmaster General awarding contracts to the lowest

“responsible” bidder, vice the traditional “lowest bidder.”

“Responsible” was defined as those carriers who had carried mail over

a route of at least 250 miles for a period of at least six

months. This had the instant effect of eliminating the smaller

carriers who were having difficulty surviving and were shipping bricks

to pad their incomes. In mid May of 1930, Brown summoned the heads

of the major airlines to his office and briefed them on his plans to

reshape their industry, through mergers, to improve economies of scale

and to avoid competition between companies serving the same markets

(!!). The airline heads had little choice, since Brown controlled the

awards of their air mail contracts. Unable to agree among themselves

how to divide up the national route structure, they asked Brown to act

as umpire and decide for them what appeared in the best interests of

the Department. Brown proceeded over a matter a weeks, to define what

became the “big four” U.S. airline companies, American, Eastern,

United, and TWA. Gone were the small carriers such as Robertson in

St. Louis and Ludington in Philadelphia.

What the well-dressed air mail pilot wore, and didn’t wear!

Dick Merrill, a well-known air mail pilot, liked to fly the hot, humid

southern routes of CAM 19 in his shorts, gun, parachute, helmet, and

goggles. Photo: Editor’s Collection

These major airline companies completed expansion of commercial

passenger and mail service to all four corners of the continental

U.S. and achieved sufficient financial stability to invest in their

own research and development programs in partnership with aircraft

manufacturers and national laboratories pursuing aeronautical

sciences, such as the Guggenheim Laboratories at MIT, Princeton, and

Cal Tech. There followed advances in multiengine airframe design and

construction, radial engine design, constant speed variable pitch

propeller design, and gyro-based cockpit instrumentation that was

needed for nighttime and weather flying. By 1933, United had funded

Boeing to produce the Model 247, and TWA had countered by funding

Douglas to produce the DC-2. American pioneered their overnight

transcontinental passenger sleeper service with an order from

Curtiss-Wright for the Model T-32 Condor II (see Skyways

- and #84).

Keeping the air mail safe was serious business and pilots often

carried sidearms to enforce that. One wonders what was so important

in the air mail on this NAT Carrier Pigeon to warrant protection by

U.S. Marines armed to the teeth! Photo: Editor’s Collection

But, despite what appeared to be benevolent dictatorial steering of

the airline industry by the Postmaster General’s office, to the

betterment of the air transportation of the general public, the winds

of political change and unrest among the smaller air carriers began to

cause opposition in the public news media. The stock market crash of

October, 1929, and the ensuing Great Depression in the American

economy that was felt around the globe, precipitated a swing in

political leadership toward a Democrat, Franklin D. Roosevelt, as

President in 1933. At the urging of Senator Hugo Black of Alabama,

FDR promptly appointed his own Postmaster General, one James

T. Farley, with strong encouragement to sweep the Department clean of

any public appearance of government collusion and profiteering in the

airline industry (References 1-3). Black’s hearings on the air mail

in the Senate opened on February 2, 1934, with unsubstantiated

accusations of government collusion thrown at former Postmaster Brown

and toward the Department of Commerce, wherein resided the Bureau of

Air Commerce which regulated aircraft design and manufacturing

standards. Those who refused to open their accounting books to the

Senate were sentenced to jail terms for contempt. The scene got ugly

and became a public news spectacle on street corners and in movie

theaters.

Army Air Mail, Part TWO

On February 9th, 1934, head of the Army Air Corps, Major General

Benjamin B. Foulois, was summoned to the White House to meet

personally with the President. FDR was very upset about the Senate

hearings and wanted to defuse that situation promptly to regain public

confidence in the Depression-ridden administration. Without

exchanging niceties, the President asked the General, point blank,

“Can your Air Corps fly the air mail?” With flashbacks to the 1918

tasking of Reuben Fleet to create an Army Air Mail overnight, Foulois

reasoned that he too was faced with little choice and responded in the

affirmative, like a good soldier, and like a hopeful leader toward

better funding support for his struggling peacetime Air Corps.

Shortly after returning to his office that same day, Foulois was

served with Executive Order Number 6591, directing that

the Army immediately take over the U.S. Air Mail as an emergency

measure, with full cooperation of the Post Office Department, the War

Secretary, and the Secretary of State. On February 19th, the Post

Office cancelled all existing air mail contracts, sending a shock wave

throughout the aviation industry. No criminal charges had ever been

proven, yet the government was punishing the very corporate structure

it had hastily created during the Hoover administration. Airline

leaders such as Eddie Rickenbacker of Eastern, and D.W. Tomlinson of

TWA took to public microphones and news cameras expressing their

outrage, to no avail. The die had been cast in the oval office, and

the Air Corps was once again in the breech, ready or not, just like in

1918.

When the Army Air Corps was directed to fly the air mail in

1934, a wide variety of aircraft were used ranging from fighters to

large bombers such as this Douglas B-7 seen here on Air Mail Route 18

between Salt Lake City, Utah and Oakland, California. Photo: Editor’s

Collection

Foulois immediately passed the word down through his chain of command,

directing his area commanders to take over regions of the air mail

route structure, using military observation aircraft, fighters, and

bombers, as were at hand in local squadrons. Bomb bays in Martin

B-10s became mail bins with the bomb racks removed and the belly doors

safetied shut. Crews of open cockpit fighters like the Boeing P-12,

and attack planes like the Curtiss A-12 began stuffing sacks of mail

around the pilot’s feet and behind the pilot’s seat. On the P-12, the

only space available was a tiny stowage area behind the cockpit,

which, loaded with mail, made for an aft center of gravity and a

dangerous lack of longitudinal stability. The Army clearly lacked the

proper aircraft and the proper cockpit gyro instrumentation, as well

as the pilot instrument proficiency, to undertake this new air mail

directive around the clock, in fair weather or foul. Within days,

there were front page photos of fatal crashes of Army mail planes

almost every other day. It was a man made slaughter of dedicated

young military pilots, in peacetime, simply to serve a political

purpose. FDR became more embarrassed by the Army Air Mail debacle

than he had been over the Black hearings in the Senate earlier that

year. And what action was taken in the oval office this time? FDR

simply called General Foulois back onto the carpet and blamed the

entire mess on his inadequate leadership of the Army Air Corps

(References 1-5).

The other end of the Army spectrum, also seen here on

A. M. Route 18, were fighters that had very little air mail capacity

such as this Boeing P-12E. Photo: Editor’s Collection

On June 1, 1934, a sheepish Roosevelt administration ended the Army

Air Mail emergency service and returned the responsibilities back to

the contract air mail carriers. In later years, retired General

Foulois tried to put a better face on his being abused by the

executive branch, and stated that the Army Air Mail tragedy of 1934

was actually a godsend, for it awakened the American public to the

needs in training and equipment in the Air Corps that served to shore

up our air defenses in time to bounce back from the attack on Pearl

Harbor in 1941. Always, the good soldier, to the bitter end.

Loading the mail into an Eastern Air Transport Condor 18. With

improvements in airplanes, navigation, communication, airports, and

weather forecasting in the .30s, carrying the air mail became routine,

and the risk and adventure of the early days, just a memory. Photo:

Editor’s Collection

References

- Glines, Carroll V. The Sage of the Air Mail, Van Nostrand

Company, Inc., Princeton, NJ 1968. - Shamburger, Page, Tracks Across the Sky, Lippincott

Company, Philadelphia and New York, 1964. - Neilson, Dale, Saga of the U.S. Air Mail Service, Air Mail

Pioneers, Inc., 1962. - Courney, W.B., “The Wreck of the Air Mail,”, Collier’s

magazine, February 9, 1935, page 10 and following. - Allen, Oliver E., The Airline Builders, Time-Life Books,

Alexandria, VA 1981. - Rosenberg, Barry, and Macaulay, Catherine, Mavericks of the

Sky, HarperCollins Publishers, New York, 2006.

- Deliver and maintain services, like tracking outages and protecting against spam, fraud, and abuse

- Measure audience engagement and site statistics to understand how our services are used

- Improve the quality of our services and develop new ones

- Deliver and measure the effectiveness of ads

- Show personalized content, depending on your settings

- Show personalized or generic ads, depending on your settings, on Google and across the web

Click “Customize” to review options, including controls to reject the use of cookies for personalization and information about browser-level controls to reject some or all cookies for other uses. You can also visit g.co/privacytools anytime.